9 Power and progress

Roberts on Acemoglu and Johnson

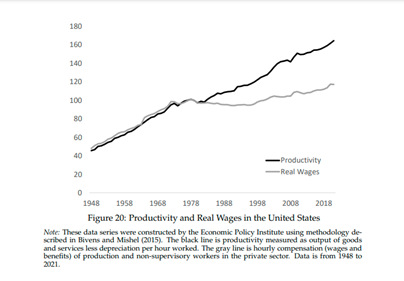

‘Power and Progress – a thousand- year struggle over technology and prosperity’. This book does not give us much chapter and verse in empirical evidence of the impact of technology on productivity growth or on the incomes of the many as opposed to the few.

Instead, in Power and Progress we get a sweeping historical account of how technology has taken humanity forward in terms of living standards but also often created misery, poverty and increased inequality.

Acemoglu and Jonson ask the question: “Aren’t we more prosperous than earlier generations, who toiled for a pittance and often died hungry, thanks to improvements in how we produce goods and services?” They answer: “Yes, we are greatly better off than our ancestors. Even the poor in Western societies enjoy much higher living standards today than three centuries ago, and we live much healthier, longer lives, with comforts that those alive a few hundred years ago could not have even imagined. And, of course, scientific and technological progress is a vital part of that story and will have to be the bedrock of any future process of shared gains.”

But they argue that this was not an automatic (sic) result of technology, but rather “shared prosperity emerged because, and only when, the direction of technological advances and society’s approach to dividing the gains were pushed away from arrangements that primarily served a narrow elite. We are beneficiaries of progress, mainly because our predecessors made that progress work for more people. As the eighteenth-century writer and radical John Thelwall recognized, when workers congregated in factories and cities, it became easier for them to rally around common interests and make demands for more equitable participation in the gains from economic growth…. Most people around the globe today are better off than our ancestors because citizens and workers in early industrial societies organized, challenged elite-dominated choices about technology and work conditions, and forced ways of sharing the gains from technical improvements more equitably.”

Acemoglu and Johnson point out the ‘industrial revolution’ in Britain and later in Europe and the United States did not lead to a rise in average real incomes for most workers until well into the second half of the 19th century.

They concur with the analysis of Friedrich Engels in his book, The condition of the working class in England, written in 1844, that as hand weavers and workers in other handcraft sectors lost their jobs to machines in the cities, they were pauperised while rural workers and their families coming to the cities to work in factories were paid a pittance.

It took the rise of labour organisations, government legislation and the beginnings of some welfare distribution to bring about a significant rise in comes, according to the authors.

They also point out that “The Gilded Age of the late nineteenth century was a period of rapid technological change and alarming inequalities in America, like today. The first people and companies to invest in new technologies and grab opportunities, especially in the most dynamic sectors of the economy, such as railways, steel, machinery, oil, and banking, prospered and made phenomenal profits…. Businesses of unprecedented size emerged during this era. Some companies employed more than a hundred thousand people, significantly more than did the US military at the time. Although real wages rose as the economy expanded, inequality skyrocketed, and working conditions were abysmal for millions who had no protection against their economically and politically powerful bosses. The robber barons, as the most famous and unscrupulous of these tycoons were known, made vast fortunes not only because of ingenuity in introducing new technologies but also from consolidation with rival businesses. Political connections were also important in the quest to dominate their sectors.”

This is all the same shades of the late 20th century and now.

The book considers what can be done to ensure that the gains from the productivity ‘bandwagon’ of modern technology like robots, automation and AI can be spread among the many and not just garnered by the few.

Acemoglu and Johnson reckon that “technology advancements are usually seen by managers with business-school educations as opportunities to reduce wages and cut labor costs, because of the lingering influence of the Friedman doctrine—the idea that the only purpose and responsibility of business is to make profits.” This is naïve – surely capitalist businesses’ main aim is to make profits – that’s the point. It is not the ideology of Friedman that drives this, but the necessary drive for profits delivers the ideology of Friedman.

As the authors point out, contradictions arise under a mode of production for profit: “The problem is an unbalanced portfolio of innovations that excessively prioritize automation and surveillance, failing to create new tasks and opportunities for workers. Redirecting technology need not involve the blocking of automation or banning data collection; it can instead encourage the development of technologies that complement and help human capabilities.” But under capitalism, it does not do so.

The authors studiously avoid the obvious policy conclusion that if most of the gains from technology go to those with the power, then to spread those gains, technology needs to be owned and controlled not by tech oligarchs but by the many through common ownership.