8 USA

Smith

In the late 80s and 90s, it felt like we were on the cusp of a great shift, where the back-slapping jocks who had dominated American society in earlier times were on the verge of losing power and status to the bespectacled freaks and geeks. The Revenge of the Nerds was coming.

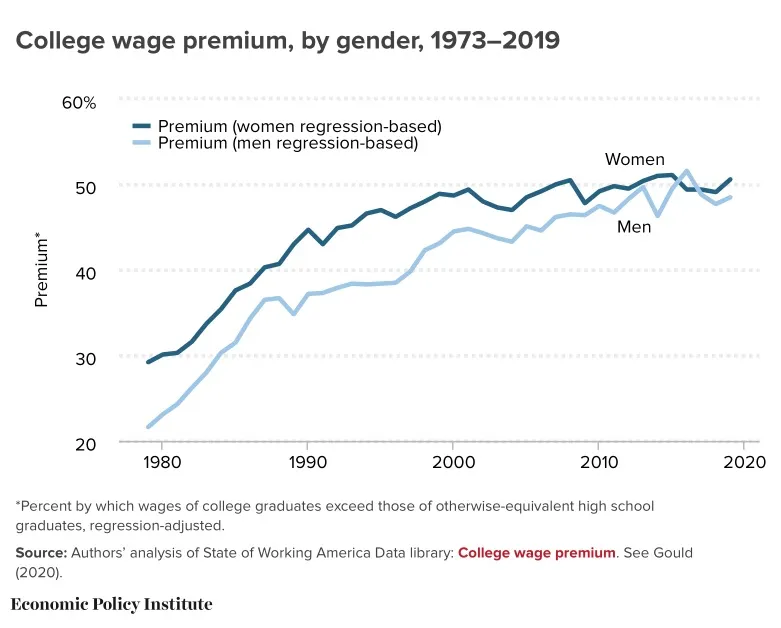

It wasn’t just fantasy, either. Over the next thirty years, the nerds really did win the economic competition. The U.S. shifted from manufacturing to knowledge industries like IT, finance, bio, and so on, effectively going from the world’s workshop to the world’s research park. This meant that simply being able to cut deals and manage large workforces were no longer the only important skills you needed to succeed at the highest levels of business. Bespectacled programmers and math nerds became our richest men. From the early 80s to the 2000s, the college earnings premium rose relentlessly, and a degree went from optional to almost mandatory for financial success. The age of human capital was in full swing, and the general consensus was that “Average Is Over”.

That trend lasted so long that most Americans can no longer remember anything else. We’ve become used to the idea that technology brings inequality, by delivering outsized benefits to the 20% of society who are smart and educated enough to take full advantage of it. It’s gotten to the point where we tacitly assume that this is just what technology does, period, so that when a new technology like generative AI comes along, people leap to predict that economic inequality will widen as a result of a new digital divide.

And it’s possible that will happen. I can’t rule it out. But I also have a more optimistic take here — I think it’s possible that the wave of new technologies now arriving in our economy will decrease much of the skills gap that opened up in the decades since 1980.

AI coming

A whole lot of research is being done on the productivity effects of generative AI tools, and they all seem to conclude the same thing: Generative AI gives a much bigger boost to low performers than to high performers.

No study so far showing that more talented people are able to use generative AI more effectively than less talented people. All of the evidence points to generative AI as an equalizer.

It’s not hard to think of why this might be the case. Whereas previous forms of information technology complemented human cognition, generative AI tends to substitute for human cognition.

Traditional IT acted like a shovel — something that complemented people’s natural abilities — while generative AI acts more like a steam shovel. A steam shovel handles the muscle-power for you; GPT-4 handles the detail-oriented thinking for you. Technologies that substitute for natural ability tend to make natural ability less scarce, and therefore less valuable.

This doesn’t mean generative AI will decrease inequality overall. The computation-intensive nature of these tools means that physical capital — access to large amounts of cheap GPUs or other key hardware — might make a comeback as a source of wealth. But by boosting the performance of the least skilled on cognitive tasks, generative AI looks like it could level the human-capital playing field.