15 China

China basically destroyed every idea western intellectuals had about economic growth and development. Practically nobody admits how embarrassing this is for economists and political scientists.

(Yuen Yuen Ang)

I think Acemoglu’s focus on democracy and non-extractive institutions is a bit of outlier in the growth lit, which mostly would contend that China’s high levels of average human capital and physical capital investments should lead to substantial growth.

I think China actually is democratic and non-extractive at the local level, something that Acemoglu misses by focusing on national stuff. A big part of the post-Mao reforms was turning local development over to local governments and making them accountable for performance.

To be honest China since Deng Xiaoping has followed the Fredrich List- Alexander Hamilton form of political economy. They are following the same policies from Meiji Japan and Imperial Germany.

Godfree Roberts (Writes ‘Here Comes China’ Newsletter)

When Mao stepped onto the world stage in 1945 his country was convulsed by civil war, Russia had taken Mongolia and a piece of Xinjiang, Japan still occupied three northern provinces, Britain had taken Hong Kong, Portugal Macau, France pieces of Shanghai, Germany Tsingtao, and America dominated the opium trade.

In 1949 China was agrarian, backward, feudalistic, ignorant and violent. Of its four hundred million people, fifty-million were drug addicts, eighty percent could neither read nor write and life expectancy was thirty-five years. Peasants paid seventy percent of their produce in rent, women’s feet were bound, desperate mothers sold their children in exchange for food and poor people, preferring slavery to starvation, sold themselves. U.S. Ambassador John Leighton Stuart reported that, during his second year in China, ten million people starved to death in three provinces. The Japanese had killed twenty-million and General Chiang Kai-Shek wrote that, of every thousand youths he recruited, barely a hundred survived the march to training base.

By 1974 Mao had doubled the population, doubled life expectancy, reunited, reimagined, reformed and revitalized the largest, oldest civilization on earth, modernized it after a century of failed modernizations, liberated more women than anyone in history and ended thousands of years of famines. A strategist without peer, political innovator, he was a master geopolitician and a Confucian peasant, under crushing embargoes Mao had grown GDP by 7.3 percent annually and left the country debt-free.

Harvard’s professor of Chinese Studies, John King Fairbanks, summarized[1] his legacy: “The simple facts of Mao’s career seem incredible: in a vast land of 400 million people, at age 28 with a dozen others to found a party and in the next fifty years to win power, organize, and remold the people and reshape the land–history records no greater achievement. Alexander, Caesar, Charlemagne, all the kings of Europe, Napoleon, Bismarck, Lenin–no predecessor can equal Mao Tse-tung’s scope of accomplishment, for no other country was ever so ancient and so big as China. Indeed Mao’s achievement is almost beyond our comprehension”. [Fairbanks, The United States and China].

Looking back through the lens of economic habits, practices, stats and reports, we can impute the scale of Mao’s achievement. He’s called the founder of modern China because he designed and laid the foundation on which the economy and civil society rests. In doing so, he rejected, for example, the Soviet practice of building gigantic, centralized industrial facilities in the name of ‘efficiency’ and instead created the most decentralized (to this day) economy on earth. And that’s less than 1% of his foundational role.

These three articles examine each of Mao’s most famous campaigns:

http://www.unz.com/article/mao-reconsidered/?highlight=mao

http://www.unz.com/article/mao-reconsidered-part-two-whose-famine/

http://www.unz.com/article/the-great-proletarian-cultural-revolution/

(Comment to https://branko2f7.substack.com/p/four-historico-ideological-theories-628)

Tooze

This China that we are casually generalizing about, is a state whose population is the same as that of North America, South. America and all of Europe put together, under almost 80 years of uniquely transformative rule by a historically unique and still dynamic political party that directly inherits the DNA of the revolutionary era and self-consciously orientates itself towards avoiding the fate of the only regime to which it can, at a pinch, be meaningfully compared, namely the Soviet Union.

Tooze (2023) Whither China? Regime impasse

15.1 China as Supplier of Intermediate Goods

Smith

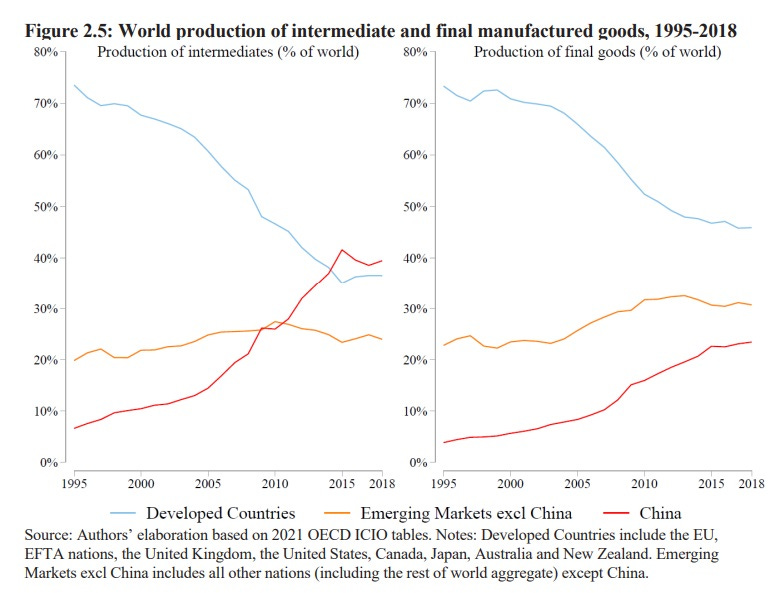

Americans tend to think of China selling consumer goods to Wal-Mart and such, but this isn’t that important of a story. In fact, China is much more powerful in terms of exporting intermediate goods — parts, materials, and machinery:

China produces around 40% of all the intermediate goods in the entire world! China’s importance as a supplier to the U.S. manufacturing sector has skyrocketed in recent decades.

But we make most of our inputs ourselves. China only makes about 4.4% of the intermediaries for the U.S. electronics manufacturing industry, 5.1% for vehicle manufacturing, and so on.

If the developed democracies want to restore their manufacturing prowess, they need to focus on intermediate goods. And if the U.S. wants to “friend-shore” its supply chains, it should focus on intermediate goods. This means we should use more subsidies and fewer tariffs, since tariffs on intermediate goods are especially harmful to domestic manufacturing (which is a topic for a longer post).

The fact that U.S. manufacturers don’t actually use that many imported inputs to begin with means that reshoring will probably be a lot easier than the doubters imagine. We’re talking about maybe 3.5% to 5% of inputs here. That’s not a lot, and it won’t be that costly to onshore or friend-shore.

15.3 China zigzagging

Michael Roberts

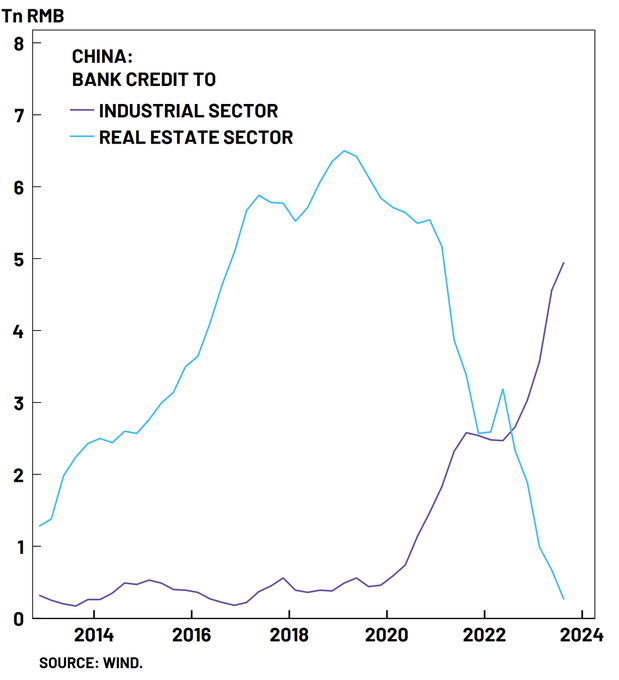

The real challenge for China’s economic future is how to avoid much of its investment going into unproductive areas like finance and property. It is China’s large capitalist sector that threatens China’s future prosperity.

Michael Roberts (20223) China zigzagging

China’s economy is seriously ‘imbalanced’. There is ‘too much’ investment in such projects and not enough handouts to the people to spend on consumer goods like I-phones or services like tourism and restaurants. China cannot grow any more unless it switches households from saving to spending and investment to consumption. The old state-led investment and export model is dying. China will now end up like Japan, stagnating with near zero growth and a falling population.

I have pointed out the nonsense of this view on several occasions. China’s growth has been based on a high rate of productive investment – at least until the unproductive capitalist property development sector came overloaded with debt.

Michael Roberts

In the main IIPPE conference there were other presentations on China. I’ll single out just two. The first was again by Prof Dic Lo, called The Political Economy of China’s “New Normal”. This dealt with a key question being posed in the Western media – namely is China’s recent economic slowdown permanent, or even worse is it a signal of China’s imminent demise? Prof Lo considers whether the slowdown is due to a lack of domestic demand, as many Keynesian experts on China like Michael Pettis claim, or is it due to falling profitability of capital in China, as Marxists might suggest? Lo tends to argue for the latter as the main cause (indeed I find the same in my own study of this – see the book, Capitalism in the 21st century, pp213-14).

But Lo points out that industrial sector profitability remains high; it is the profitability of unproductive sectors like real estate and the stock market that has fallen back – and we know that China is facing a real estate crisis. Also, profitability has fallen because of a rising share of wages in value added (unlike in the West) and a rise in the organic composition of capital, following Marxist theory.

For me, Lo’s paper poses the major contradiction in China’s weird, hybrid economy. If the profitability of capital falls, that reduces investment and productivity growth in the capitalist sector. For me, that increases the need for China to expand its state sector to make the economy not so dependent on profitability, particularly in technology, education and housing.

Michael Roberts (2023) IIPPE 2023 Part Two – China, profitability and financialisation

15.4 Housing

Tooze

43 percent of all homes in China had been built since 2010, 68 percent since 2000 and 88 percent since 1990. If you put this in relation to total population it implies that in a single generation, China has built enough homes to house a billion people.

It is the demand for concrete and steel generated by this giant construction boom that has made Chinese growth so dirty. It is important to emphasize this point. As a driver of energy consumption, the rehousing of hundreds of millions of people, dwarfs China’s role as an exporter.

What China needs is not more physical construction but a burst of institutional state-building. What China needs is a welfare state adequate to its new status as a high-middle income country and that will require a new fiscal constitution.

Tooze (2023) Can Beijing halt China’s housing avalanche?

Roberts

‘Productive’ investment growth has fallen back in China. Investment in new technology, manufacturing etc has given way to investment in unproductive assets, particularly real estate. In my view, successive Chinese governments made a big mistake in trying to meet the housing needs of its burgeoning urban population by creating a housing for sale market, with mortgages and private developers being left to deliver. Instead of local governments launching housing projects themselves to house people for rent, they sold state assets (land) to capitalist developers who proceeded to borrow heavily to build projects. Soon housing was no longer “for living but for speculation” (Xi quote). Private sector debt rocketed – just as in the real estate bubble in the West. It all came to a head in the COVID pandemic as developers and their investors went bust. The real estate crisis has remained unresolved.

What the Chinese government needs to do is take over these large developers and bring them back into public ownership, complete the projects and switch to building for rent. The government should end debt payments to foreign investors and only meet obligations to small investors; and transfer housing out of the mortgage and private finance system.

The real estate sector has got so large in China as a share of investment and output that it has seriously degraded overall growth. This is where the economy does need rebalancing.

China’s private sector has mushroomed in the last two decades. It has led to an unhealthy expansion of billionaires and rising inequality of wealth and incomes. And just as in the West, as the profitability of productive capital fell, the capitalist sector switched into unproductive investment areas, like finance and real estate. Debt has rocketed. This has increased the risk of economic crises as in the West.

Contrary to the views of the Western experts and Li, it’s not less investment and more consumption; not less public and more private investment that China needs to sustain its previous economic success, but the opposite.

15.5 Global Integration

Benjamin Selwyn

At least since President Barack Obama’s pivot to Asia, have responded by formulating political, economic, and military strategies to constrain China’s rise.36 This containment strategy represents an attempt to maintain China in a semi-peripheral position by forestalling its attempts at becoming part of the core of the world economy. As Minqi Li puts it, “although China has developed an exploitative relationship with South Asia, Africa, and other raw material exporters, on the whole, [it] continues to transfer a greater amount of surplus value to the core countries in the capitalist world system than it receives from the periphery.”

Selwyn (2023) Limits to Supply Chain Resilience: A Monopoly Capital Critique

15.6 Ming, Qing and the Century of Humiliation

Noah Smith

The Ming and Qing dynasties that ruled China from 1368 to 1911. The conventional wisdom is that during this period, China turned its back on the outside world and on new technologies, choosing instead to look inward and cultivate a tranquil, harmonious, static society. The Ming burned their oceangoing ships in the 1500s and sealed the country off from most trade. In 1793, the Qing emperor declared to a British trade mission that “Our Celestial Empire [has] no need to import the manufactures of outside barbarians.” That isolationism was brought to an abrupt end when China’s technological backwardness and military weakness made it incapable of resisting foreign aggression in the 1800s, leading to the “century of humiliation”.

15.7 Turchin’s Model applied to China

Milanovic

Turchin’s model applies to China (not discussed in the book) probably as well as to America. The relative immiseration of the median class has gone on for the past forty years. Indeed, it went hand-in-hand with its phenomenal increase in material well-being, to the clip of almost 10% per year, and is thus less noticeable. At the top end of the distribution, the political/administrative class that has historically ruled China is opposed, still very cautiously, by the rising capitalist/merchant class. In a paper by Yang, Novokmet and Milanovic, we have documented and analyzed probably the most radical change —short of a revolution—in the composition of the elite ever. That has occurred in China between 1988 and 2013. Economic growth has displaced the administrative class in favor of those linked with the private sector (capitalists).

15.8 Investment switch

This is probably one of the most important charts right now about the Chinese economy. To offset the collapse in the real estate sector, Beijing has managed to surge credit to the manufacturing sector, which has helped prevent a total collapse of domestic credit growth and demand

15.9 Maoism

Milanovic

If one were to define Maoism as a pragmatic application of Marxist principles to bring about a revolution to China, get rid of “landlordism” and feudal institutions, and liberate China from undue foreign influence, it was indeed a great success. But if one were to look at Maoism as an “exportable” ideology, it was a failure. Maoism in the world, as opposed to Maoism in China, could best be described as the ideology of a senescent classical left-wing movement that lost faith in working class revolutionary potential and hated bureaucratized socialism of the Soviet Union. But it produced almost nothing that is intellectually challenging or durable.

Milanovic (2021) A global ideology that was neither

Wagner

China’s growth and emissions problems have a common source: unproductive investment. Although China is still a middle-income country with abundant high-return projects, investment in the last decade has been concentrated in the property sector. Accounting for up to 25% of GDP in the 2010s, housing investments went far beyond the needs of China’s urbanizing middle class. Local governments’ encouragement of developers, coupled with cheap finance from state-owned banks, fueled a property bubble that sucked in resources that would have been put to better use in other economic sectors. This bubble now appears to be deflating, dragging down consumer confidence and risking a classic deleveraging spiral, similar to what the West faced after the subprime-mortgage bubble burst in 2008.

The remedy is simple: share the benefits of growth more widely. Chinese consumption represents only 40% of GDP, which is among the lowest rates the world, and well below the US. China’s weak social safety net compels Chinese households to save large amounts of their income, which gets funneled directly into domestic investment by a state-directed financial system. Meanwhile, artificially low bank interest rates, rising public-sector consumption, and other policy choices deliberately tamp down household consumption and push up investment.

Removing these macroeconomic distortions would benefit not only Chinese households, but also the planet. Chinese investment has been hugely costly for the climate. China uses half of the world’s steel and coal, and 60% of its cement. All those apartments, roads, and bridges require enormous amounts of energy and carbon-intensive materials.

Slowing the rate of investment in physical capital would curb some of this outsize damage to the climate. Moreover, as incomes rise, Chinese consumers will shift their spending proportionally to services. Around the world, as households grow richer, they tend to spend more on health care, education, and hospitality, and less on carbon-intensive products. This iron law of development will further slow China’s emissions growth, allowing it to bend the curve downward through concerted decarbonization efforts.

China will need to slow the growth of overall electricity demand in order to phase out coal and cut CO2 emissions. The result will be a full decoupling of economic growth from growth in energy demand and, thus, CO2 emissions. From a climate perspective, China’s next economic chapter cannot come soon enough.

15.10 Chinese loans

Roberts

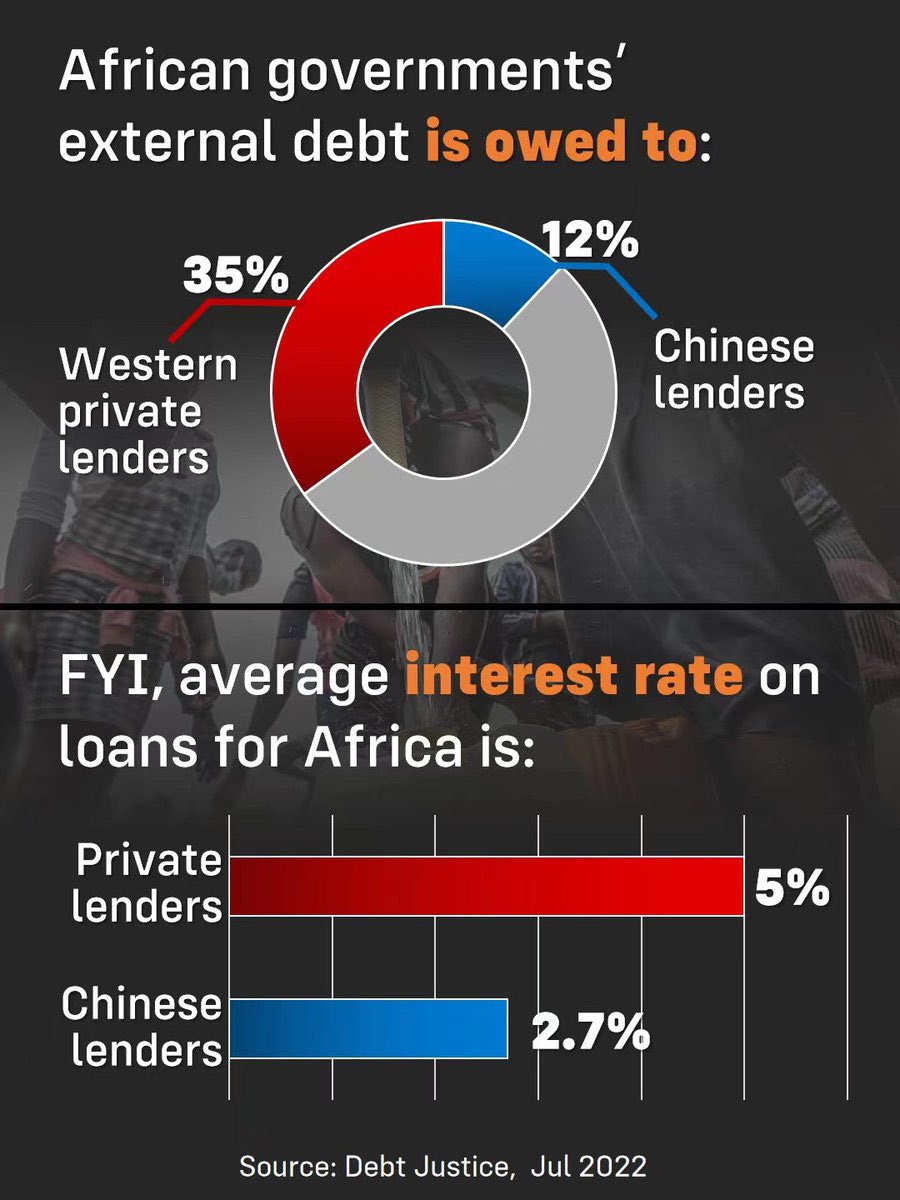

China is not a particularly large lender to poor countries compared to Western creditors and the multi-national agencies.

15.11 China’s Rise

Farooqi

The world economy in the late-twentieth century had a tripolar advanced industrial core centered on the United States, Western Europe and Japan. This structure has since been transformed by the rise of China. The Asian production network used to be centered on Japan as late as 2000. This hub-spoke system has since recentered on China.[1] And whereas the Asian core used to be smaller than the Western cores in the late twentieth century, Asia has now taken the leading position. Indeed, Asia already accounts for more than half of global manufacturing value-added, while Europe and America together account for less than a third. More precisely, China accounts for 30 percent, Asia ex. China another 17 percent, while Europe and America account for 16 percent of global manufacturing value-added each. Let that sink in: China is as large an industrial power as Europe and America combined.

China’s economy may still be smaller than America’s at market exchange rates, but it is already larger than the European Union’s. Moreover, Chinese living standards have begun to converge with those of the advanced economies. Real per capita income at purchasing power parity in China increased from $3,452 in 2000 to $18,188 in 2022—a rate of growth of 8.2 percent per annum. Over the same period, real per capita income grew at 1.2 percent per annum in the US and 1.3 percent per annum in the EU.

The Chinese economic miracle has not only transformed the network topology of the global production system and the core-periphery structure of the world economy, it has also changed the polarity of the international system.

The rise of China as the dominant industrial power in the world cannot fail to transform the strategic balance.

The United States cannot assume that it can outgun China by outspending it. So, before we initiate a long and costly cold war, we need to think very carefully about what we’re getting ourselves into.

A power transition is underway in world politics. Gilpin’s motor of world history—the law of uneven growth—continues to churn.

15.12 Climate Finance

Tooze

China’s domestic climate finance mobilization was greater than that of all other countries combined, accounting for 51% of all domestic climate finance globally. Even without greater detail, we can therefore conclude that at least as far as domestic resource mobilization is concerned, China’s spending exceeds its one third share of global green house emissions, is, perhaps, three times greater than its share of historic emissions and twice its share of global GDP.

China success in driving this extraordinary pace of investment relies on a combination of centralized and decentralized mechanisms.

About half of the solar panels added this year will be installed on rooftops, largely driven by China’s “whole county solar” model, where a single auction is carried out to cover a targeted share of the rooftops in a county with solar panels in one fell swoop.

Under this model, the developer negotiates with building owners and arranges contracts with the grid, financing, procurement, contracting and installations. This model – which could be described as centralised development of distributed solar – has enabled rooftop solar deployment at a vast scale.

The other half of solar installations are set to be in large utility-scale developments, particularly in the gigawatt-scale “clean energy bases” in western and northern China.

Tooze (2023) Carbon Notes 6: China’s lead in the energy transition

If the pace of new low-carbon capacity installation in China is dramatic, the expansion of the upstream capacity to actually manufacture low-carbon energy technology is even more so.

What has unleashed this extraordinary surge in investment? Carbon Brief is worth quoting at length:

The announcement of the 2060 carbon neutrality target provided the political signal, but wider macroeconomic conditions have delivered low-carbon capacity growth far in excess of policymakers’ targets and expectations, with this year’s solar and wind installation target met by September and the market share of EVs already well ahead of the 20% target for 2025.

The clampdown on the highly leveraged real-estate sector, starting in 2020, led to a steep drop in the demand for land, commodities, labour and credit for apartments and associated infrastructure. This left a hole in the finances of local governments – which rely on land sales for a lot of their revenue – and hit economic growth rates.

Local governments were, thus, searching for alternative investment opportunities to drive economic growth. Yet, at the same time, their investment spending was under scrutiny due to debt concerns. China’s high-level environmental and industrial policy goals made cleantech one of the acceptable sectors for their investment.

At the same time, the government made it easier for private-sector companies to raise money on the financial markets and from banks, as part of measures to stimulate the economy during the pandemic.

The low-carbon energy sector, in contrast with the fossil fuel and traditional heavy industries, is largely made up of private companies. Access to credit had earlier been a major bottleneck for them in a financial system that has heavily favoured state-owned firms.

As a result, much of the bank lending and investment that previously went into real estate is now flowing to manufacturing – largely cleantech manufacturing – as well as to cleantech deployment.

Local government enthusiasm for attracting investments to their regions meant that they often also offered major direct or indirect subsidies. Reportedly, it is common for local governments to build an entire factory and associated infrastructure, with the private company going on to occupy the site only covering the cost of machinery and operations.

All of this happened at a time when falling costs driven by technological learning and subsidies resulted in many low-carbon energy technologies becoming economically competitive against fossil fuels.

China’s policymakers had favoured “green” investments previously, as in the 2009 stimulus package launched in response to the global financial crisis. Yet the sector had been too small to absorb the huge amount of credit mobilised as a part of China’s stimulus cycles. After experiencing extremely rapid growth since 2020, this has changed.

The construction of low-carbon energy manufacturing capacity, production of low-carbon energy equipment and construction of railways have been significant drivers of commodity demand this year, as the only areas of investment showing substantial growth.

This demand explains, among other things, why China’s steel output has continued to grow despite the ongoing contraction in real-estate construction.

Conversely, the precipitous drop in demand for commodities from the real estate and conventional infrastructure sectors explains why the breakneck expansion of low-carbon energy sectors – and their commodity demand – has not resulted in a spike in prices.

The coincidence of the real estate collapse since 2021 and the green energy boom means that China has become the first large economy in which the green energy transition is driving growth at the macroeconomic scale. In the medium-term this must irrevocably change its political economy, with green energy interests coming to the fore. So large is the shift in China that talk of being in mid-transition (Grubert, Hastings-Simon) does not seem far-fetched. But, as Carbon Brief notes, the major test is still to come.

Politically, the major challenge will only come when low-carbon energy begins to substantially cut into the demand for coal and coal-fired power.

This shift threatens the interests of the coal industry and local governments with a high exposure to the coal sector. These stakeholders could be expected to resist the transition, raising concerns about potential roadblocks.

15.14 Monetary

Roberts

The government has just announced that its new Central Financial Commission will take over from the People’s Bank and the existing financial regulator, the control of China’s financial private sector. The ‘Western experts’ decry this move because they think the market can better allocate investment than the state. “The temptation to intervene in capital and credit allocation, whether arising from risk or management failure, or from political directive, is likely to be elevated,” said perennial China sceptic, George Magnus. He added. “These features do not augur well for China’s financial stability or economic prospects.”

The point is that the Xi leadership no longer trust the Western-educated economists in the People’s Bank to regulate the private sector – the bank is a fortress of neo-classical pro-market economics. The bank’s economists would support Magnus’ approach to free up the finance sector – something so successful in Western economies! But the CP leaders still stop short of bringing these speculative financial and real estate speculators into public ownership (no doubt some leaders have personal links). Until they do, financial speculation will continue to distort the economy much more than any arbitrary policies of the party leaders.

15.15 Currency

Smith

China’s currency, the RMB (typically called the yuan), has, with a few brief interruptions, been getting cheaper and cheaper relative to the U.S. dollar for the past decade:

Of course, some of the reason for the depreciation of the yuan is based on lower expectations of future growth. But some of this is probably due to China’s policy of keeping the yuan from appreciating a bunch in the bullish times (which it does by having its central bank buy U.S. bonds). And some of it is a macroeconomic response to Trump’s tariffs in late 2018; tariffs tend to push down the exchange rate of the country subject to the tax, thus offsetting some of the effects of the trade barrier.

And remember that a cheap yuan makes China’s exports more competitive vs. the exports of the United States. Thus, a combination of macroeconomic weakness and exchange rate management is helping China gain and hold market share in all the industries that the U.S., Europe, and the rest of Asia would like to build up. In other words, part of what you’re looking at when you see that graph above is a story about slowing Chinese growth, but part of it is about increasing Chinese competitiveness. It would be helpful to remember that.

Smith (2023) Is China really falling behind the U.S. economically?

De Mott

China has more foreign exchange reserves than reported, a former Treasury official wrote.

An additional $3 trillion is hidden in "shadow reserves," such as state commercial and policy banks.

"Not everything that China does in the market now shows up in the PBoC's balance sheet."Half of China’s currency reserves are “hidden,” a situation that may add risks to the global economy down the road, former Treasury Department official Brad Setser wrote.

While the country’s State Administration of Foreign Exchange reported $3.12 trillion in foreign assets last December, Setser estimates that foreign exchange reserves actually sit at around $6 trillion.

“China is so big that how it manages its economy and currency matters enormously to the world,” he wrote in The China Project. “Yet over time the way it manages its currency and its foreign exchange reserves has become much less transparent – creating new kinds of risks for the global economy.”

A key indicator about China’s reserves is a sudden pause in its reported activity. From 2002 to 2012, China’s foreign exchange reserves steadily rose as the central bank bought US dollar assets to prevent China’s yuan from appreciating too much, allowing exports to remain cheap.

But over the last 10 years, China’s reserves stopped rising, which is puzzling as China’s trade surplus has continued growing, and currently stands at an all-time high, he said.

Setser, who previously was deputy assistant Treasury secretary for international economic analysis and is now senior fellow for international economics at the Council on Foreign Relations, has an idea of what’s going on.

Just as China has ‘shadow banks’ — financial institutions that act like banks and take the kind of risks that a bank might normally take but aren’t regulated like banks — China has might be called ‘shadow reserves.’ Not everything that China does in the market now shows up un the PBoC’s balance sheeet.

China’s state banking system is the main way Beijing hides its reserves, Setser said. That includes state commercial lenders like the Bank of China, Industrial & Commercial Bank of China or ICBC, China Construction Bank, and the Agricultural Bank of China as well as policy banks like the China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China.

China’s State Administration of Foreign Exchange did not immediately respond to Insider’s request for comment.

The vast amount of China’s reserves carries enormous weight in financial markets and represents a risk.

For example, Setser said China’s earlier accumulation of US Treasurys and agency bonds — such as Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae securities — helped give rise to the 2008 financial crisis, by pushing investors further into riskier mortgage-backed securities.

“China’s lack of transparency here is a bit of a problem for the world,” he said. “China structurally is so central to the global economy that anything it does, seen or unseen, will eventually have an enormous impact on the rest of the world.”

De Mott (2023) China is hiding $3 trillion of foreign currency in ’shadow reserves

15.16 The Big Inundation

Welsh

On a personal level, this feels weird, in that all the things I’ve been warning about for decades are now happening. De-dollarization, industrial hollowness leading to military incapacity, and the Global South abandoning Europe and American en-masse.

Slowly, then quickly.

I mean, it’s not weird, these things were obvious. But 30 years is a long time in a human life. To see it all happening now, just as I (and others) predicted feels really weird.

Same as climate change: for a long time we were warning, and not it’s here in ways only fools can deny. Exactly as predicted. I always said it would happen sooner and worse than the IPCC claimed.

The Chinese are going to get in the neck, of course. They’ll get lead-trace and then be gutted by climate change and ecological collapse like everyone else. Their time in the sun will be brief.

It’s Chinese bad luck to make it to the top of the industrial heap at the moment when the entire industrial stack is about to become impossible to maintain. They played by the industrialization rules, and they’re going to die by them.

Still, unless the North China breadbasket gets wiped out an early inundation, the Chinese will probably hold on longer than most. Big if, though. My money is that a big inundation will hit far sooner than most models say.

Welsh (2023) China Will Be Understood To Be The World’s Premier Power In Less Than A Decade

15.17 Left Government China Ride

Welsh

Back in 2016 I wrote a piece called “Seven Rules For Running a Real Left Wing Government.” It proved to be one of my most popular pieces, particularly loved by activists. Since then I’ve often been asked for an more and I’ve finally written a partial update and companion piece.

The Sixth Rule was “Reduce Your Vulnerability to the World Trade System.”

What working with China can do for you.

Movement up the industrialization chain;

Modernization

one time infrastructure

cheap loans

Training and teching-up your scientists, engineers and designers.

To take advantage of this opportunity you need to understand China’s domestic issues:

China has far more construction and development capacity than it needs. It has built most of the buildings, roads, ports, hospitals, schools, power plants and so on it requires. China could get rid of those jobs and cut the industry in half OR it could use it overseas and not throw a pile of people out of work and destroy half an industry. This means, among other things, that China is willing to put up infrastructure for very low prices in order to keep the people employed.

China has a vast need for resources: food, fuel, minerals and so on. If you’ve got it, odds are they need it and they want long term secure deals.

China is moving up the manufacturing value chain and moving into services. In many cases the Chinese government has forced industries to shut down low value manufacturing plants that are still profitable. They want the lower chain industry out of their country, and over time what counts as “lower” moves further up the chain.

What all this means is that China is willing to build your country what it wants for cheap in exchange for deals for your resources and, more importantly, to relocate industry to your country.

Welsh (2023) How To Use China To Make Your Left Wing Government Succeed

15.19 Nuclear

Barnard

China couldn’t recreate the conditions for success despite having every ability to so. Their nuclear program peaked in 2018 with seven reactors achieving commercial operation but has been averaging three reactors a year since. This year the single reactor that’s been connected to the grid may not achieve commercial operation. In my assessment, their industrial export strategy led them to build too many technologies and designs of reactors instead of rigorously enforcing a single design, hamstringing the deployment and scaling effort.

Barnard (2023) What Drives This Madness On Small Modular Nuclear Reactors?

COP28 Triple Nuclear Pledge

Wesoff

Ironically absent from the pool of signees is China, the only country with any real chance of meeting the COP goal. China aims to double its nuclear energy capacity by 2035 and is well on its way; as of this year, 22 nuclear plants are under construction in China with more than 70 planned.

Wesoff (2023) 20-plus countries pledge to triple the world’s nuclear energy by 2050

15.20 SOE -State Owned Enterprises

Tooze

China’s SOEs are a core pillar of the world’s second-biggest economy, accounting for 66 per cent of gross domestic product in 2023, Tsinghua University public policy experts Zhang Fang and Zuo Jialu wrote in February. And in energy, size matters. The SOEs have the resources and backing to develop at scale China’s best wind and solar resources in the remote north-west, areas where smaller private sector groups have struggled to operate. Another feature of Chinese policymaking is that leaders’ publicly stated targets are seldom missed. The investment drive in renewable energy, coupled with China’s rapid transport electrification, means many international experts now forecast that China’s emissions peak will probably occur sooner than 2030. And the implications of this green turn by China’s SOEs go beyond the high-level climate targets. Whereas once the groups were known for being deeply conservative, they are investing more in new, unproven technology, including start-ups. “They are actually on the edge of trying out new technologies and putting those into commercial use,” said Yicong Zhu, senior renewables and power analyst at Rystad Energy. This is boosting private sector research and development efforts at a time of capital market weakness, and means that China is well placed to extend its global lead across key clean technologies. In one example cited by CEF, the China State Shipbuilding Corporation is developing the largest prototype offshore wind turbine in the world, with the rotor 260 metres high and powering about 40,000 households.