40 North Korea

Smith

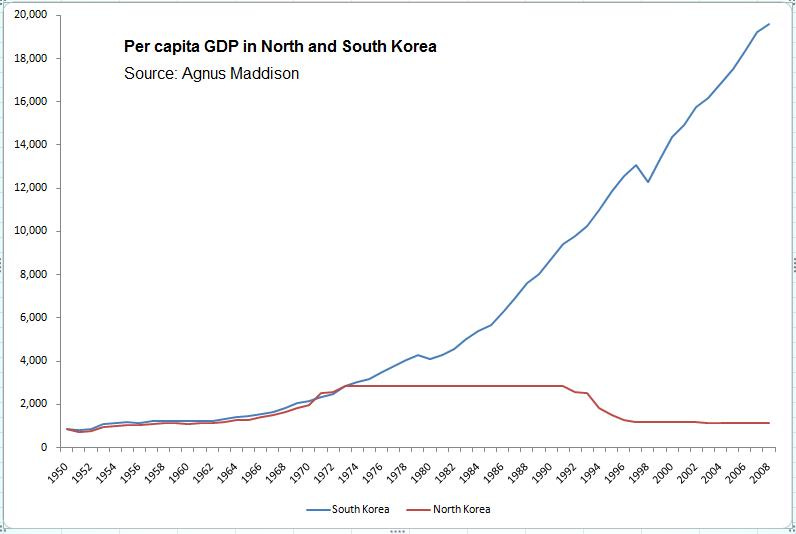

One explanation, beloved of leftists, is that the U.S. simply bombed North Korea back to the stone age 70 year ago, and it remained there. This isn’t credible. Even if you believe the bombing of North Korea was more destructive than the devastation of South Korea — whose capital changed hands three times during the war — it still doesn’t fit with North Korea’s timeline. In fact, until the early 1970s, North Korea was growing at a decent clip, and keeping pace with South Korea.

Obviously these figures are hard to know exactly, and the perfectly straight line for North Korea between 1973 and 1992 just means “we don’t have any data for this period”. But in 1965, the economist Joan Robinson was praising North Korea’s rapid economic growth and successful rebuilding efforts:

Eleven years ago in Pyonygang there was not one stone standing upon another. (They reckon that one bomb, of a ton or more, was dropped per head of population.) Now a modern city of a million inhabitants stands on two sides of the wide river, with broad tree-lined streets of five-story blocks, public buildings, a stadium, theaters (one underground surviving from the war) and a super-de luxe hotel. The industrial sector comprises a number of up-to-date textile mills and a textile machinery plant. The wide sweep of the river and little tree-clad hills preserved as parks provide agreeable vistas. There are some patches of small gray and white houses hastily built from rubble, but even there the lanes are clean, and light and water are laid on. A city without slums.

So what happened in the 70s? Well, for one thing, North Korea embarked on a massive military buildup in order to reduce its military dependence on Russia and China. This diverted resources from investment in the civilian economy. North Korea also borrowed a bunch of money internationally and invested heavily in mining; when it was hit hard by a long decline in the price of metals in the 70s, 80s, and 90s, it was unable to pay its foreign debts and had to default. That, along with the collapse of the USSR in 1991 — which had provided North Korea with large amounts of aid and trade — provided a long-running macroeconomic shock that took a lot of time to recover from.

Juche

North Korea has always been one of the world’s most centrally planned economies; extreme central planning can be good for conducting a war or rebuilding from a war, but otherwise tends to misallocate resources by quite a lot. There is some optimal level of central planning, and North Korea simply exceeded it. The principle of “juche” (self-reliance) also discouraged North Korea from both exporting manufactured products — which was one of the main ways South Korea improved its productivity and got rich — and importing goods that could have been used as inputs into domestic production.

Western sanctions have also been a factor in North Korea’s economic isolation, but probably less than people think. Most sanctions are very recent, and are due to the country’s nuclear program; before that, North Korea actually exported a lot of minerals. Meanwhile, China doesn’t impose sanctions and in fact trades with North Korea a fair amount, though thanks to China’s mercantilist policies and North Korea’s general industrial backwardness, North Korea runs a large trade deficit and mostly just sells China minerals. Meanwhile, North Korea has generally resisted efforts by South Korea to expand economic ties.

In other words, North Korea’s poverty is really not hard to explain. When you’re a small country and you close yourself off to trade and you intentionally mismanage your domestic economy, you’re going to be poor. If the U.S. could reach out to North Korea and help ease it out of its paranoia, the situation might change. That’s unlikely, but we did just do it with Vietnam, so maybe there’s hope.