22 Germany

Tooze

The story of the German labour market miracle is in large part a myth.

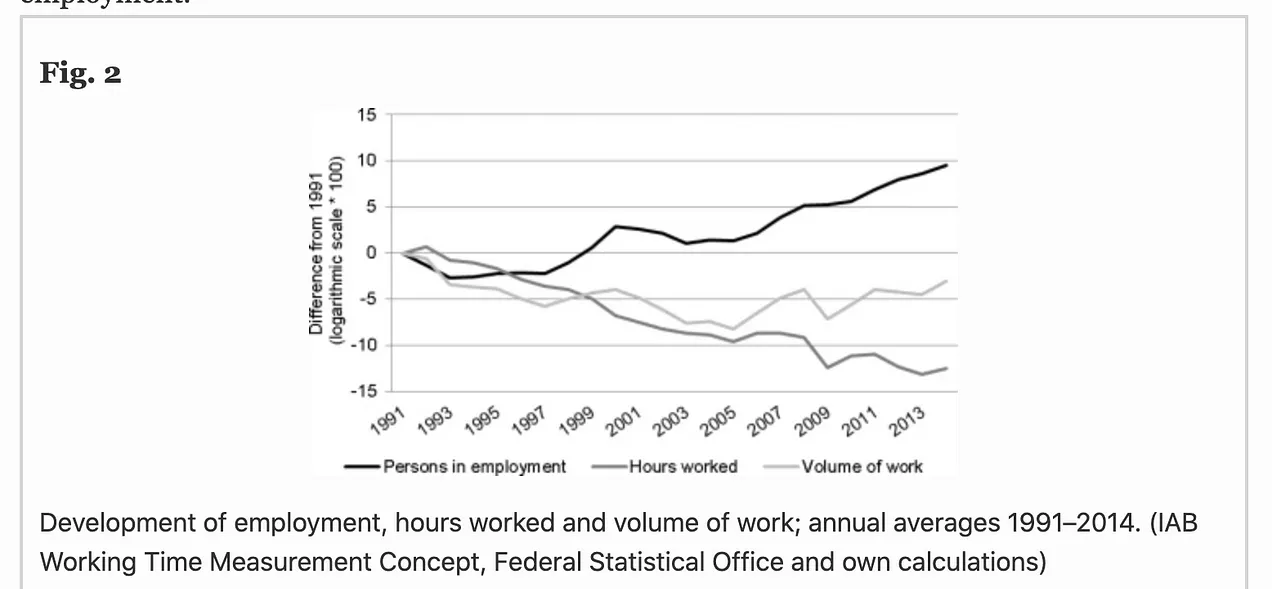

The early 2000s labour market measures did not increase the overall supply of labour, they really just hustled millions of people into dead-end, part-time jobs. Work was redistributed and spread more thinly to the disadvantage of workers.

Over the period from the late 1990s to the 2010s, full-time employment declined and part-time work and self-employment increased dramatically. Overall, comparing the 2010s relative to 2000 the total input of labour was flat, relative to the early 1990s it was down. One can have different opinions about a more flexible as opposed to more standards form of employment, but it certainly increased inequality and it did not increase overall labour input, which cannot, therefore, have been a major driver of GDP growth.

Between the late 1990s and 2006 full-time employment in Germany suffered a real crisis. The number of jobs contracted by almost 25 percent. It then stabilized at this much lower level. Amongst the self-employed likewise the hours of work declined and then stabilized. What the Hartz IV labour market measures may perhaps be credited with, is not so much an industrious revolution that propelled growth, as a stabilization. As hours of work in the full-time sector stabilized, more and more people were absorbed into part-time work. This had the effect of returning the total labour input of the economy to its 2000 level. This reduced the number of those who were classed as unemployed and suffered the associate stigma. An unprecedentedly large share of the population, including many more women, were brought into one or other form of employment.

The labour supply as such is not a constraint on the German economy, the unwillingness to invest in people - in their education, housing, supportive social services, job security - is. That is good news and puts the ball squarely back in the court of Germany’s political parties who must overcome the deadlock over debt and public investment - calling for a major investment push in Germany.

Germany …is truly a case of what Keynes would call “muddle”, a self-inflicted injury as a result of a failure of societal coordination, organization, mobilization and persuasion. It is an authentically political problem.

Tooze (2023) Chartbook 242: What is wrong in Germany? And an (interesting) correction.

Milanovic

What were the topics that fueled the pessimism? Here is an approximate list: inflation and dearness of energy, economic stagnation (near zero growth), the rise of the extreme right, political paralysis, loss of exports to China, decline of German car technology, high wealth inequality, imperfect assimilation of foreign-born population, inefficiency of German railways, dark streets in Berlin (saving of energy), full political dependence on the US.

I think that the pessimistic mood dominates not only because of the current wars in Ukraine and in Israel/Palestine, and general uncertainty that has enveloped the world, and Europe in particular, but because of the resonance of current concerns with the events from one hundred years ago in Germany. It seemed to me that the current events played on three important German fears: runaway inflation, wrecking of democracy, and the rise of antisemitism. All three are grounded in the Weimar period, and like a person who has been once poisoned, the fear of a similar outcome is not assessed by the actual strength of the current “poison” but by past memories and the awareness that, if not entirely checked and nipped in the bud, things can get out of control.

Despite many years of social-democratic rule and an extensive welfare state, German wealth inequality is very high. 39 percent of the German population has zero (or quasi zero) net wealth, and almost 90 percent of the population has zero or rather negligible net wealth. German wealth inequality (depending on the metric one uses) equal or even greater than the very high US wealth inequality.

The full establishment of the Alternativ für Deutschland as a stable parliamentary party with about 10% of the vote, and not a passing fad like the Republicans in the past, serves as a reminder of a non-negligible chance of sharp movement to the right.

The third fear is, in a way, the most irrational but does not seem to me absent. Germany’s strong, and perhaps excessive, support for Israel in the current war in the Middle East has its obvious roots in the Shoah and the atonement for those crimes which the German public opinion and politicians have since the establishment of the Federal Republic put on a level of an almost core principle, equal to democratic governance and judiciary independence. The irony is that an excessive zeal in atonement might lead to the unquestionable acceptance of policies that lead to crimes committed against civilian populations. Germany thus faces an almost Greek-like drama: the desire to correct for past misdeeds may lead to the acceptance of current misdeeds.

Milanovic (2023) The three German fears - Historical origins of the malaise

22.1 German Christmas

Tooze

For poets, priests, and politicians–and especially ordinary Germans–in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the image of the loving nuclear family gathered around the Christmas tree symbolized the unity of the nation at large. German Christmas was supposedly organic, a product of the winter solstice rituals of pagan “Teutonic” tribes, the celebration of the birth of Jesus, and the age-old customs that defined German character. Yet, as Joe Perry argues, Germans also used these annual celebrations to contest the deepest values that held the German community together: faith, family, and love, certainly, but also civic responsibility, material prosperity, and national belonging. This richly illustrated volume explores the invention, evolution, and politicization of Germany’s favorite national holiday. According to Perry, Christmas played a crucial role in public politics, as revealed in the militarization of “War Christmas” during World War I and World War II, the Nazification of Christmas by the Third Reich, and the political manipulation of Christmas during the Cold War. Perry offers a close analysis of the impact of consumer culture on popular celebration and the conflicts created as religious, commercial, and political authorities sought to control the holiday’s meaning. By unpacking the intimate links between domestic celebration, popular piety, consumer desires, and political ideology, Perry concludes that family festivity was central in the making and remaking of public national identities.

22.2 Energy Transition

Tooze

German national CO2 emissions fell by 20 percent relative to 2022. That is a 73 million ton reduction relative to last year, bringing Germany’s total emissions to 673 m tons of CO2 equivalent, the lowest level seen since the 1950s. Emissions today are 46 percent lower than when Germany was unified in October 1990. Agora Energiwende

Coal-fired power generation fell to its lowest level since the 1960s, saving 44 million tonnes of CO₂ alone.

The 21 percent drop in emissions compared to 2022 is mainly due to the sharp decline in coal-fired power generation: lower electricity production from lignite saved 29 million tonnes of CO₂, while hard coal-fired power generation saved 15 million tonnes of CO₂.

Renewable energy production increased by 5 percent. Germany added 14.4 gigawatts of photovoltaic capacity last year, an increase of 6.2 gigawatts compared to the previous record in 2012.

Wind energy generation had a record year. This was due to favourable weather conditions and a slight increase in the number of wind turbines. At 138 terawatt hours, wind remained the largest source of electricity, producing more than all of Germany’s coal-fired power plants (132 terawatt hours). The expansion of new wind capacity remains seriously disappointing at 2.9 gigawatts. To achieve the country’s binding expansion targets for 2030, annual average wind capacity additions needs to rise to 7.7 gigawatts from 2024. Whereas in North and Eastern Germany permitting is proceeding quite smartly, in the Southern states of Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg there is a de facto stop. The new additions are coming overwhelmingly in Sachsen-Anhalt, Nordrhein-Westfalen, Schleswig-Holstein und Niedersachsen.

The forces driving the 20 percent decline in overall emissions are more complicated and ambiguous than simply a switch from dirty coal to wind and solar.

Emissions from industry fell significantly. This was largely due to the decline in production by energy-intensive companies as a result of the economic situation and international crises.

Of the 73 m ton reduction in emissions in 2023 relative to 2022, we see that 26 m was due to net reliance on electricity imports from cleaner power sources - 49 percent of German electricity imports came from hydro and wind power - and 24 percent came from nuclear power. 17 m tons was accounted for by crisis-driven cuts to German industrial production. 8 m tons was accounted for by reduced power consumption in industry, 5 m tons by broader energy efficiency. Only 6 m tons of the total, less than 10 percent, was due to the expansion of renewables. 3 m tons was due to reduced use of heavy-goods vehicles (trucks), 3 m tons due to mild weather reducing household energy consumption, 3 m tons due to long-term reductions in emissions in industry and 1 m tons came from the reduced size of animal herds.

Only about 15 percent of the CO₂ saved constitutes permanent emissions reductions resulting from additional renewable energy capacity, efficiency gains and the switch to fuels that produce less CO₂ or other climate friendly alternatives. About half of the emissions cuts are due to short-term effects, such as lower electricity prices, according to the analysis. The think tank therefore notes that most of the emissions cuts in 2023 are not sustainable from an industrial or climate policy perspective - for example, if emissions rise again as the economy picks up or if a share of Germany’s industrial production is permanently moved abroad.

CO₂ emissions from buildings and transportation remained almost unchanged in 2023, resulting in these sectors missing their climate goals for the fourth and third successive time, respectively.

Germany will likely miss its climate targets agreed under the European Union’s effort sharing regulation as early as 2024. The German government will have to compensate this failure to reach its goals by purchasing emissions certificates from other EU member states – or face fines.

According to official estimates by 2045 Germany needs to spend 310 billion Euros to almost double its transmission network from 37.000 to 71.000 kilometers. That would imply an annual construction of c. 1600 km. In fact, in the first half of 2023 only 127 km of new lines were brought into service.

Germany’s most climate-ambitious government to date currently enjoys the support of barely a third of the population.

Tooze (2024) Germany’s CO2 emissions plunge. But all is not at it seems