41 Norway

41.1 Ocean Mining

Beslik

Norway has secured a parliamentary majority for its plans to open up for deep-sea mining despite opposition from environmentalists and the fishing industry, who warn that the move risks further damage to fragile oceans.

“The renewable green industries run on minerals. This is an important contribution internationally,” said Bård Ludvig Thorheim, an MP from the main opposition Conservatives. Norway runs on oil & gas extraction.

Beslik (2023) Oil-Cave Jabs and the Dramatic Dance of Petrostates at COP28

41.2 Wealth Fund

And if Norway is so keen on renewable energy, how come they’re not investing anything in it? Norway’s sovereign wealth fund, the largest of its kind in the world at more than $1.3 trillion, has made some 10,000 investments across the global economy. Yet, it has made just three investments in renewable energy projects. Three.

Beslik (2023) Oil-Cave Jabs and the Dramatic Dance of Petrostates at COP28

41.3 Oil and Gas

41.3.1 Oil Exit Strategy

Stoknes

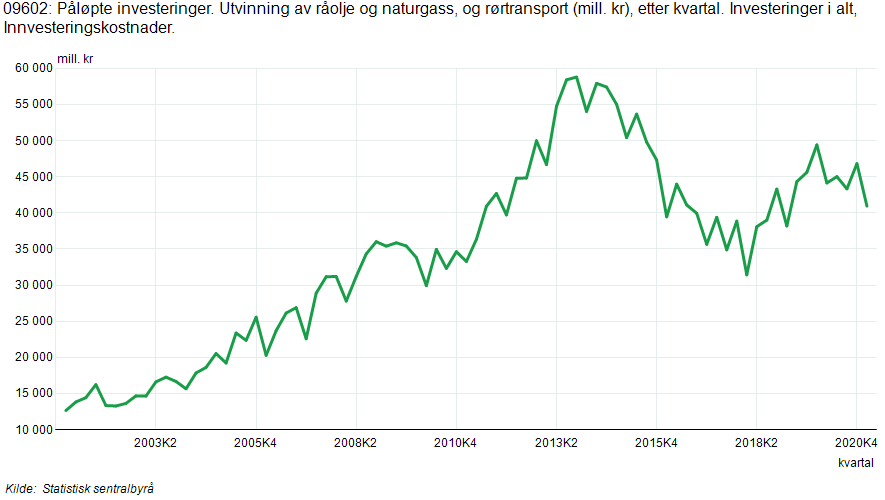

The global energy transition may usher in an age of stronger climate policies, declining oil demand and mid-to long-term low(er) oil prices. If so, oil majors as well as oil producing countries may face a trilemma in choosing between: i) maintaining high investments in the core oil and gas business, ii) preserving short-term dividend payments to shareholders and governments, or iii) investing sufficiently in the energy transition to achieve climate goals.

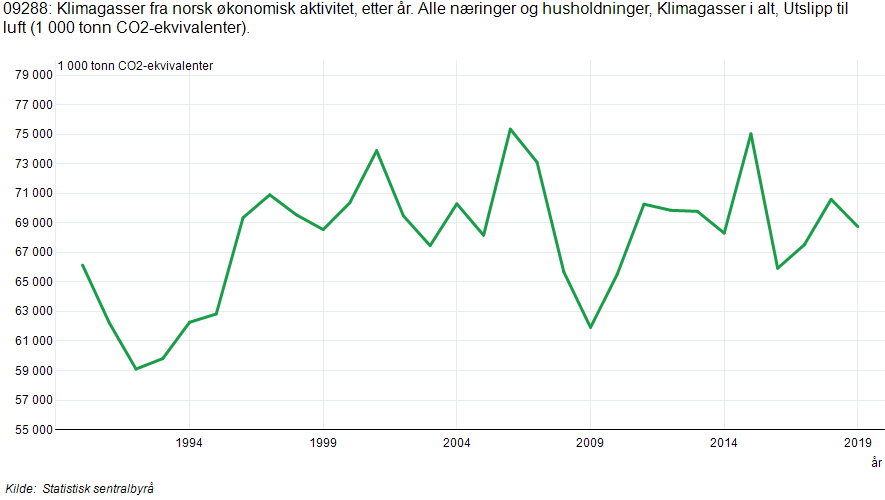

To what extent does this trilemma apply to Norway? In conclusion, our study shows that a BAU-policy with high tax incentives for petroleum production may work well economically given a long-term average of 50 $/brl for oil and 5.5 $/Mbtu for gas, or higher, to 2050 and beyond. But following this policy means that domestic climate emissions will remain high (Fig. 11), and further – as exports increasingly depend on gas sold to an EU whose green deal strategy will wean its economy off gas – is progressively risky.

Choosing a Harvest-and-exit policy is an economically more robust option in a medium-to-low oil-price world, where EU cuts down on its gas-demand as aimed for in the green deal and if the world delivers on its climate policies. This scenario delivers both a higher oil fund balance in the short and the long term, while in addition increases the likelihood of net-zero domestic emissions by 2050. But this strategy of achieving the objectives for emissions and oil fund balance comes with a trade-off of large jobs-losses (along the coast) that will incur a heavy political burden, unless countered by Rebuilding policies.

The Rebuilding policy scenario indicates that public auctions securing an investment of 30 billion NOK/yr in the construction of innovative green industrial capacity annually from 2027, incentivized through an adjusted offshore tax regime, is enough to avoid any extra decline in the offshore employment below a BAU trajectory. This, or an even Faster Rebuild policy, holds the potential to transform Norway into a low-carbon energy-exporting, economically viable society also after 2050, with an energy policy aligned with net-zero ambitions.

The implications of our study is that by adapting the GTM to their national economies and resource base, hydrocarbon producing countries can improve their understanding on the transition to green energy sectors in a world of net-zero ambitions. A set of scenarios can help foresight discourses through guidelines that focus attention on the long-term effects of current investments under uncertainty, and broaden the perspective to a better balance between future aspects of sustainability; both the economic, ecological and social.