52 Sri Lanka

52.1 Debt trap and Vulture Funds

Roberts

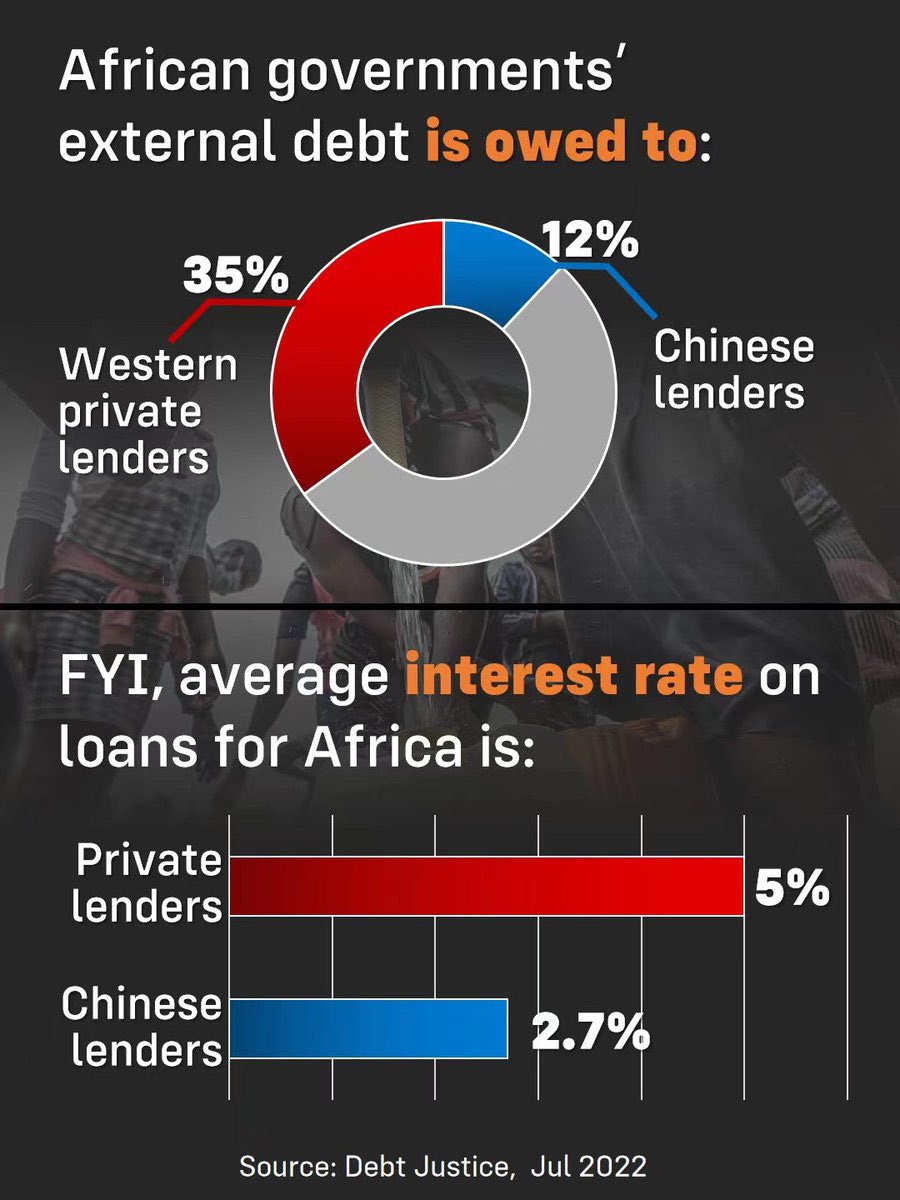

China is not a particularly large lender to poor countries compared to Western creditors and the multi-national agencies.

The rise in Sri Lanka’s debt burden was not the result of China’s ‘imperialist’ debt trap, but was caused by the desperate need of the corrupt and autocratic Sri Lankan government. After the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, interest rates fell globally, and Sri Lanka’s government looked to international sovereign bonds to further finance spending. But then COVID-19 hit, ravaging the tourism sector, a major source of income. COVID-19 required increased spending and increased imports of health and other products, exacerbating the trade deficit. Foreign currency reserves dropped by 70 percent, meaning less dollars to purchase essential yet increasingly expensive imports including fuel and commodities. To solve this, the government started to ‘print money’ to cover its deficits. . Inflation rocketed to 60 percent by June 2022. As the right-wing Chatham House study shows, “Sri Lanka’s debt crisis was made, not in China, but in Colombo, and in the international (i.e. Western-dominated) financial markets.”

By 2016, 61 per cent of the government’s sustained budget deficit was financed by foreign borrowing, with total government debt increasing by 52 per cent between 2009 and 2016. Three-quarters of external government debt was owed to private financial institutions, not to foreign governments. Despite ample warnings about the Sri Lankan economy, foreign creditors kept lending, while the government refused to change course for political reasons. This was the real nature of the ‘debt trap’.

That brings us the Sri Lankan port project, the usual issue raised about China’s supposed ‘debt trap’. China did not propose the port; the project was overwhelmingly driven by the Sri Lankan government with the aim of reducing trade costs. To quote Chatham House, “Sri Lanka’s debt trap was thus primarily created as a result of domestic policy decisions and was facilitated by Western lending and monetary policy, and not by the policies of the Chinese government. China’s aid to Sri Lanka involved facilitating investment, not a debt-for-asset swap. The story of Hambantota Port is, in reality, a narrative of political and economic incompetence, facilitated by lax governance and inadequate risk management on both sides.”

It is the obscure Hamilton Bank that is opposed to any agreement and instead is demanding full repayment on its holding of Sri Lankan bonds. Hamilton is what is called a ‘vulture’ fund’, buying up the ‘distressed debt’ of poor country governments at rock bottom prices and then pushing for full repayment at par (the original bond issue price), using the blackmail of refusing to agree to any ‘restructuring’. These vulture hedge funds specialise in sniffing out vulnerable sovereign bonds, amassing a blocking stake, waiting patiently for a broader restructuring to take place, and holding out for full repayment once a country has secured debt relief from other creditors. It’s called being a “holdout”.

Hamilton is demanding $250m in bond repayment and interest from the Sri Lankan government. The US court has intervened on behalf of the US government and other creditors to stop Hamilton getting its pound of flesh, at least until there is a general restructuring deal that Hamilton will be forced to go along with.

Even if Hamilton is thwarted and a deal with creditors is reached, Sri Lanka will still be burdened by a huge debt liability that can only be ‘serviced’ by cuts in the already low living standards of 22m Sri Lankans. The IMF has already indicated it will encourage austerity in Sri Lanka – reducing spending and increasing taxes. Sri Lanka did not seek IMF debt relief in the 1990s or early 2000s for that reason. But now it is either Hamilton or the IMF.