42 Panama

Tooze

42.1 Draught Canal

Simultaneous disruption in the Panama and Suez canals, two vital corridors for global trade, is threatening global supply chains in the run-up to Christmas. Shipowners and importers have warned that a drought in the Panama Canal and a spate of attacks on cargo vessels 11,500km away near the Suez Canal risk constraining traffic ahead of the festive season. “There are supplies that just won’t be here in time for this Christmas…”

This October was the driest in the Panama Canal region since at least 1950, according to the canal authority, partly owing to the El Niño weather phenomenon that has affected temperatures and rainfall globally. The authorities have for the first time reduced the number of crossings, which by February will be limited to only 18 ships a day. “That drought in the Panama Canal is a serious concern,” said Rolf Habben Jansen, chief executive of German group Hapag-Lloyd, the world’s fifth-largest owner of container ships, which ferry most of the world’s manufactured goods. At least 167 ships crossed the canal during the first week of December this year, compared with 238 last year…

While climate challenges trade in the Panama Canal, on the other side of the world trade is disrupted by war and its effects.

Tooze (2023) To lose one canal is careless, but two…

Yerushalmy

Over the last year, as the region has suffered through what Paton calls a “rainfall deficit”, passage through the Panama Canal has slowed and the queue of tankers waiting in the bay to pass through it has grown. Now, with warnings that the situation is set to get much worse, experts say that the effects of a restricted Panama Canal could be felt all over the world.

Connecting the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean, the canal revolutionised global shipping when it opened in 1914, eliminating the need to travel around the dangerous southern tip of South America, shortening the trip by more than 13,000km.

In 2022, more than 14,000 ships traversed the canal, transporting fuel, grain, minerals and goods from the factories of east Asia to the consumers of New York and beyond. More than 40% of consumer goods traded between north-east Asia and the US east coast are transported through the canal.

To make the journey, ships – some up to 350 metres long – enter through a narrow waterway and rise more than 26 metres above sea level into the man-made Lake Gatun through a series of locks.

The locking system relies on fresh water from Lake Gatun and another nearby reservoir to function. Every ship that passes through the canal uses 200m litres of water most of which then flows out into the sea.

The same sources also provide water for more than half of Panama’s 4.3 million inhabitants, forcing administrators to balance the demands of international shipping with the needs of the locals.

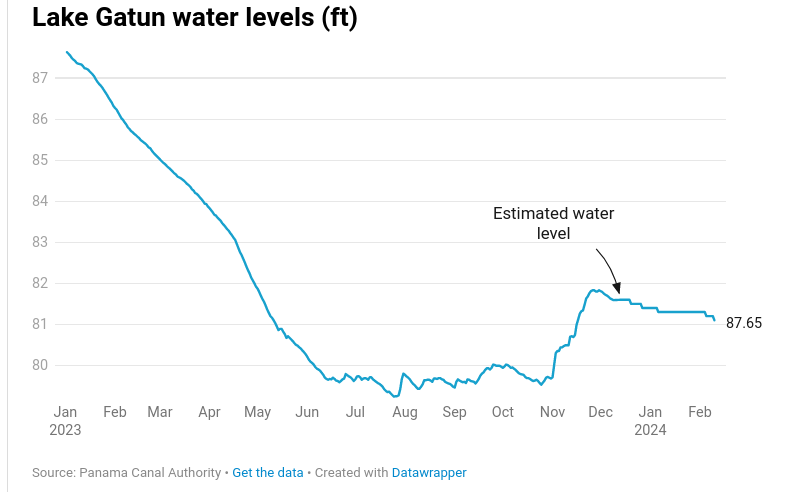

For decades, this has rarely been a problem. Panama is one of the wettest countries in the world and the canal and its surrounding lakes have been blessed with an abundance of water. However, in 2023 a rainfall deficit, exacerbated by the El Niño weather phenomenon, led to the water levels in Lake Gatun dropping.

The twin demands of the canal and the local population have left the lake facing a water deficit of 3bn litres a day.

Lake Gatun’s water level is now close to the lowest point ever recorded during a rainy season, forcing the Panama Canal authority who manages the waterway to restrict the number of vessels passing through.

In normal times, the Panama Canal has capacity to handle 36 ships a day. But as water has grown scarcer, the canal authority has reduced that number to 22. By February, it will be just 18.

With attacks on the world’s busiest trade route in the Red Sea leading many companies to avoid the Suez Canal altogether, restrictions at the Panama Canal will only pile more pressure on global supply chains – just as governments around the world attempt to tame inflation.

In the long run we’re looking at a big increase in the cost of commodities.

As the number of vessels waiting at the entrances to the canal grows, shipping experts are warning that the danger of a serious accident occurring is growing. Problems with vessels not being able to find a safe spot for anchoring. Some ships have been forced to wait at anchor for up to 25 days. If we experience any extreme weather, there could be a lot of consequential effects.

Panama’s dry season usually begins earlier than normal during major El Niño events. October this year was the driest since 1950, with 41% less rainfall than usual.

The question for the canal’s authority, global traders and the millions who rely on Lake Gatun’s reserves is whether the current water shortage is a one-off blip caused by El Niño, or a harbinger of the worst of what the changing climate could portend. The patterns we’ve come to know in the last 30 years are no longer a useful guide in helping us predict the future.

Historically there has been a [rainfall] shortage on average once every 20 years due to major El Niño events. In the last 26 years this is the third major rainfall deficit. So it seems that something is changing our rainfall patterns.

Statistically what is going on now has no analogue in the previous 100 years of data.

The canal authority says it is “implementing operational and planning procedures, innovative technologies, and long-term investments to mitigate [the] impact and safeguard [the canal’s] operation”.

Structures like the Panama Canal are miracles of the modern world – solid totems of engineering wonder that were responsible for accelerating the economic boom of the 20th century, pulling up living standards across the globe and ushering in a revolution in technology, healthcare and consumer culture.

The tacit implication was that the natural world had been tamed. But as the seas rise and temperatures soar, those assumptions are falling like dominoes.